Galerie Droste Paris

»Body without Organs«

2026

Groupshow with Antonia Freisburger, Witalij Frese and Allan Gandhi

Galerie Droste Paris

»Body without Organs«

2026

Groupshow with Antonia Freisburger, Witalij Frese and Allan Gandhi

Text

Images

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin

»Stories of Your Lives«

2025

Groupshow with Giulia Andreani, Louise Bonnet, Glenn Brown, Manuele Cerutti, Marcus Cope, Carroll Dunham, Walton Ford, Lenz Gerk, Ernest Yohji Jaeger, Ragnar Kjartansson, Sergey Kononov, Pia Krajewski, Vicor Man, Danielle Mckinney, Keita Morimoto, Paulina Olowska, Pietro Roccasalva, Jan-Luka Schmitz, Rinus Van de Velde and Joseph Yaeger

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin

»Stories of Your Lives«

2025

Groupshow with Giulia Andreani, Louise Bonnet, Glenn Brown, Manuele Cerutti, Marcus Cope, Carroll Dunham, Walton Ford, Lenz Gerk, Ernest Yohji Jaeger, Ragnar Kjartansson, Sergey Kononov, Pia Krajewski, Vicor Man, Danielle Mckinney, Keita Morimoto, Paulina Olowska, Pietro Roccasalva, Jan-Luka Schmitz, Rinus Van de Velde and Joseph Yaeger

Text

Images

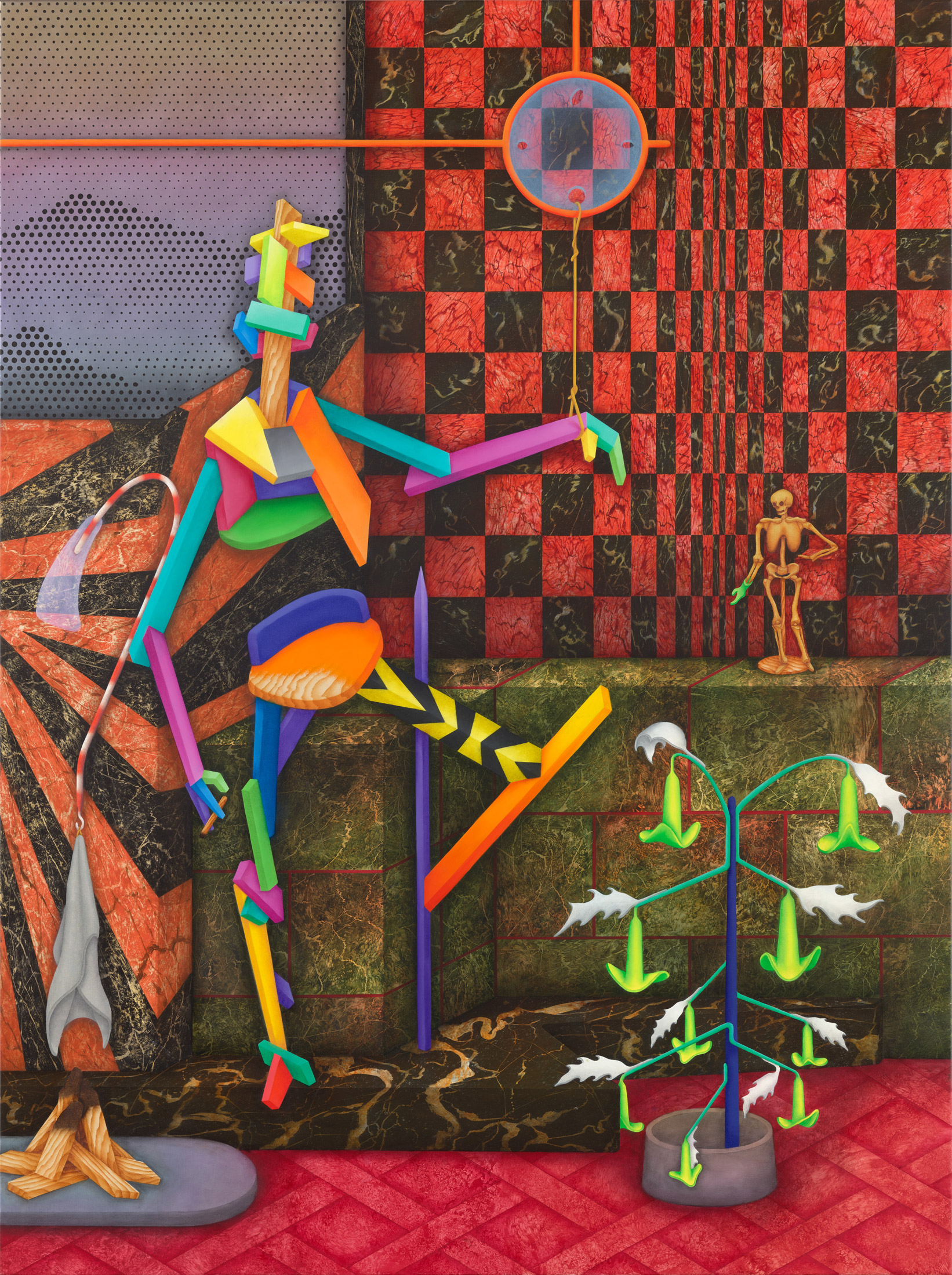

Artuner at Palazzo Capris Turin

»Supernature«

2024

Artuner at Palazzo Capris Turin

»Supernature«

2024

Text

Images

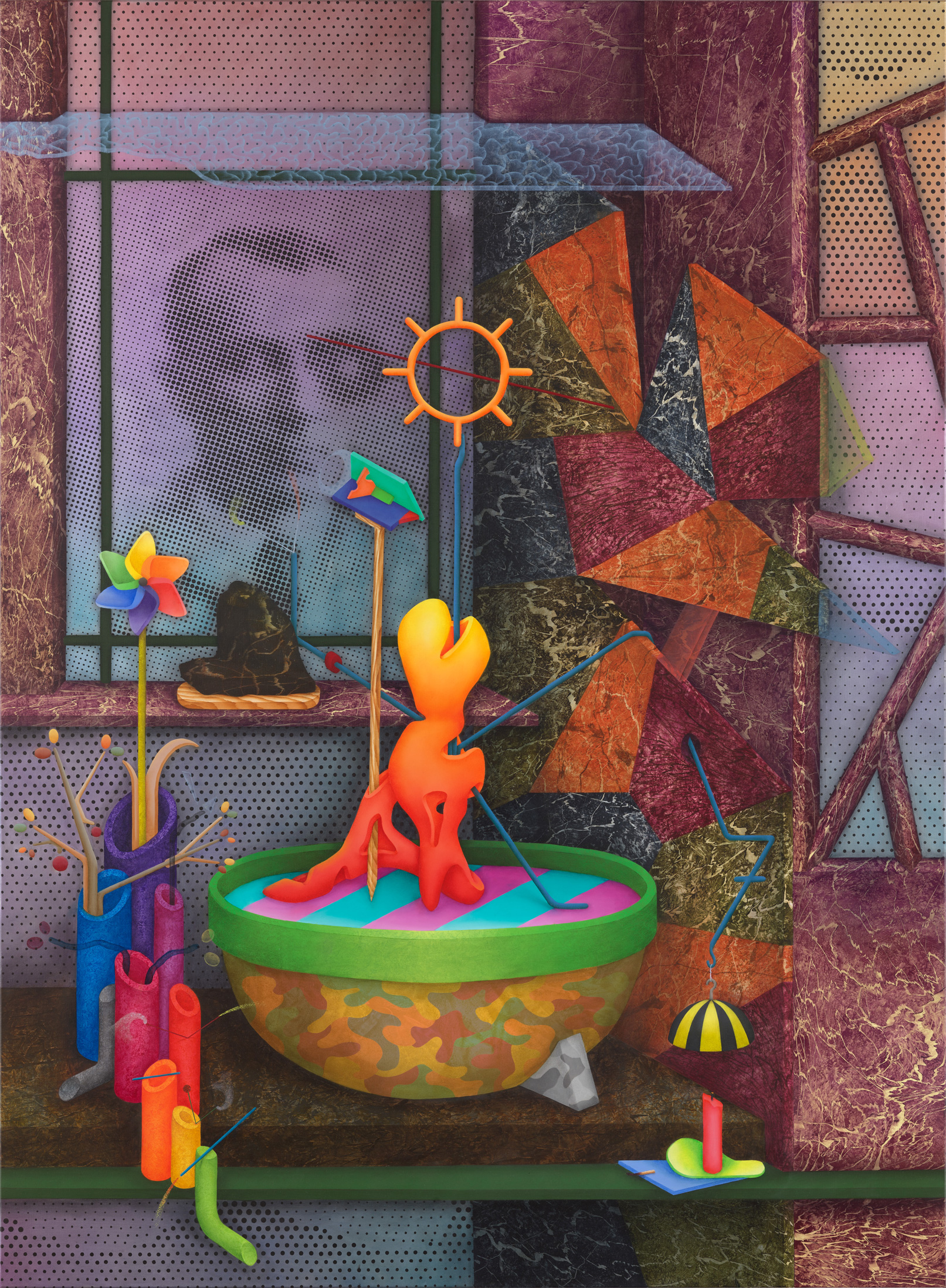

Artuner at Palazzo Coardi di Carpeneto Turin

»Dieci«

2023

Artuner at Palazzo Coardi di Carpeneto Turin

»Dieci«

2023

Text

Images

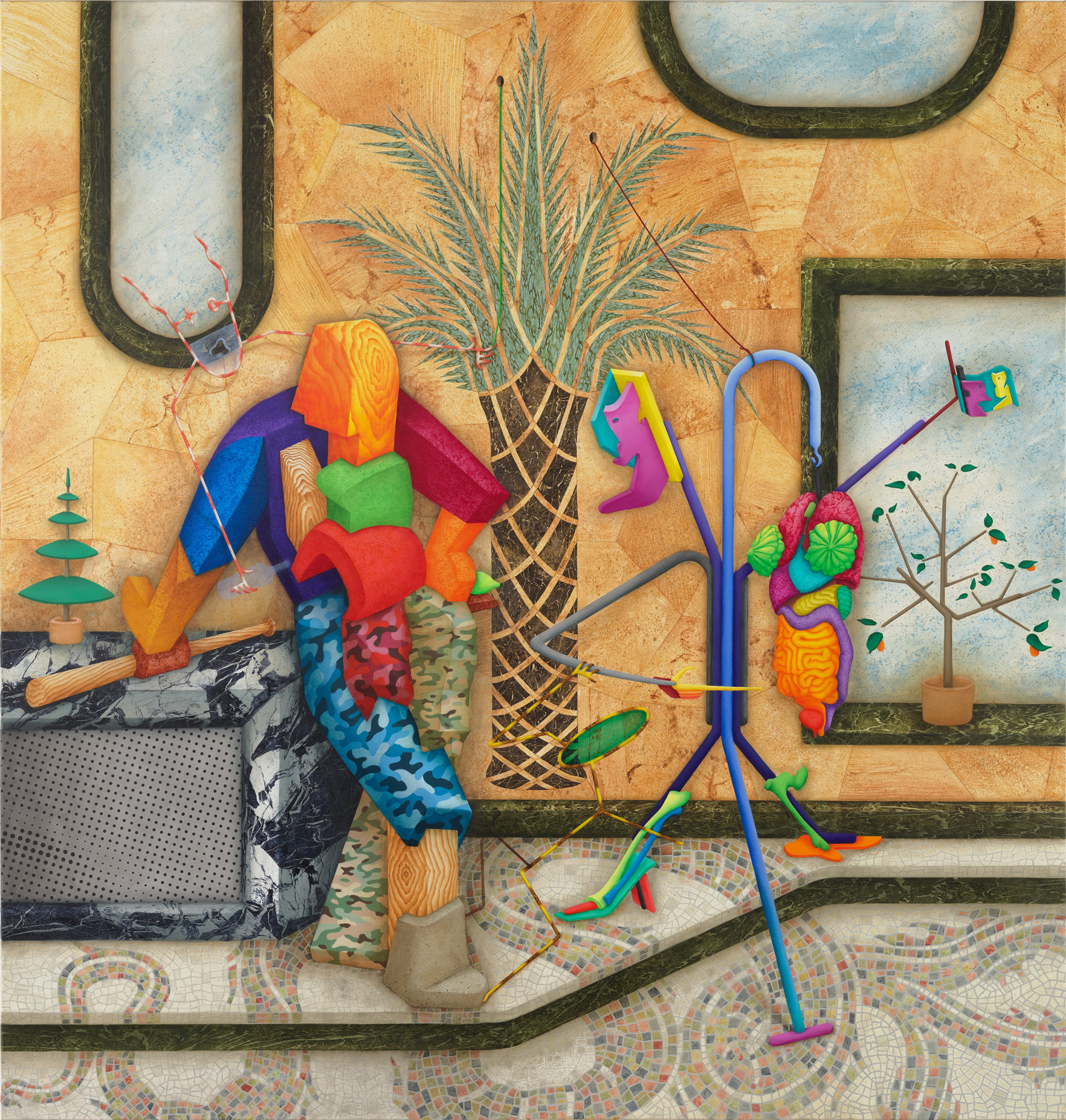

Künstlerverein Malkasten Düsseldorf

»Martedì«

2023

Künstlerverein Malkasten Düsseldorf

»Martedì«

2023

Text

Images

Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven

»The Way I See It«

2023

Catalog ISBN 978-3-9822977-5-0

Text

Images

SKD Museum Dresden

»Eppur si muove - und sie bewegt sich doch!«

2022

SKD Museum Dresden

»Eppur si muove - und sie bewegt sich doch!«

2022

Text

Images

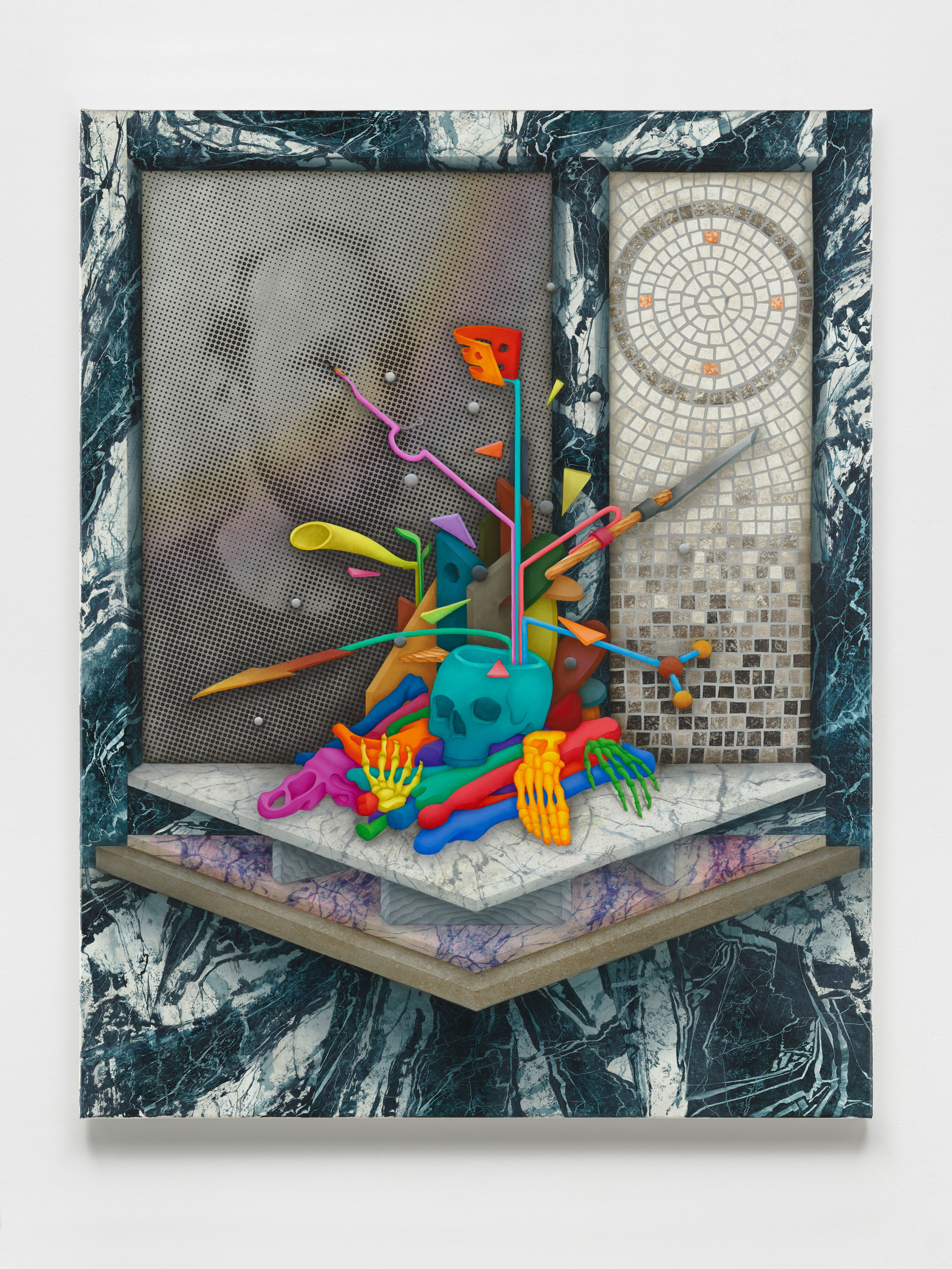

Galleria di Villa Massimo Roma

Katharina Beilstein and David Czupryn

»Jänner«

2022

Galleria di Villa Massimo Roma

Katharina Beilstein and David Czupryn

»Jänner«

2022

Text

Images

Text

Images

Text

Images

Kunstmuseum Solingen

»David Czupryn«

2020

Catalog ISBN 978-3-86206-819-7

Kunstmuseum Solingen

»David Czupryn«

2020

Catalog ISBN 978-3-86206-819-7

Text

Images

Museum Engen

»Holy Ghosts«

2019

Catalog ISBN 97-3-86206-785-5

Museum Engen

»Holy Ghosts«

2019

Catalog ISBN 97-3-86206-785-5

Text

Images

Kunsthalle Darmstadt

»He She It«

2018

Catalog ISBN 978-3-86442-263-8

Kunsthalle Darmstadt

»He She It«

2018

Catalog ISBN 978-3-86442-263-8

Text

Images

Kunstmuseum Solingen

»70. int. berg. Kunstpreis«

2016

In focus: Words by Artuner

Kunstmuseum Solingen

»70. int. berg. Kunstpreis«

2016

In focus: Words by Artuner

Text

Images

ARTUNER curated:

»Lost and found in Paradis«

Paris

2019

»Theatre of the Self«

London

2017

»Figure of speech«

New York

2016

ARTUNER curated:

»Lost and found in Paradis«

Paris

2019

»Theatre of the Self«

London

2017

»Figure of speech«

New York

2016

Text

Images